Trial Monitoring: Thomas Woewiyu

On January 30, 2014, Thomas Jucontee Woewiyu was placed under investigation in the U.S. for seven counts of crimes of perjury and two counts of fraud related to his immigration papers. On May 12 of the same year he was arrested in Newark Airport, returning from Liberia. In October, a bail was paid and he was granted temporary release before his trial under the condition that he stayed under house arrest.

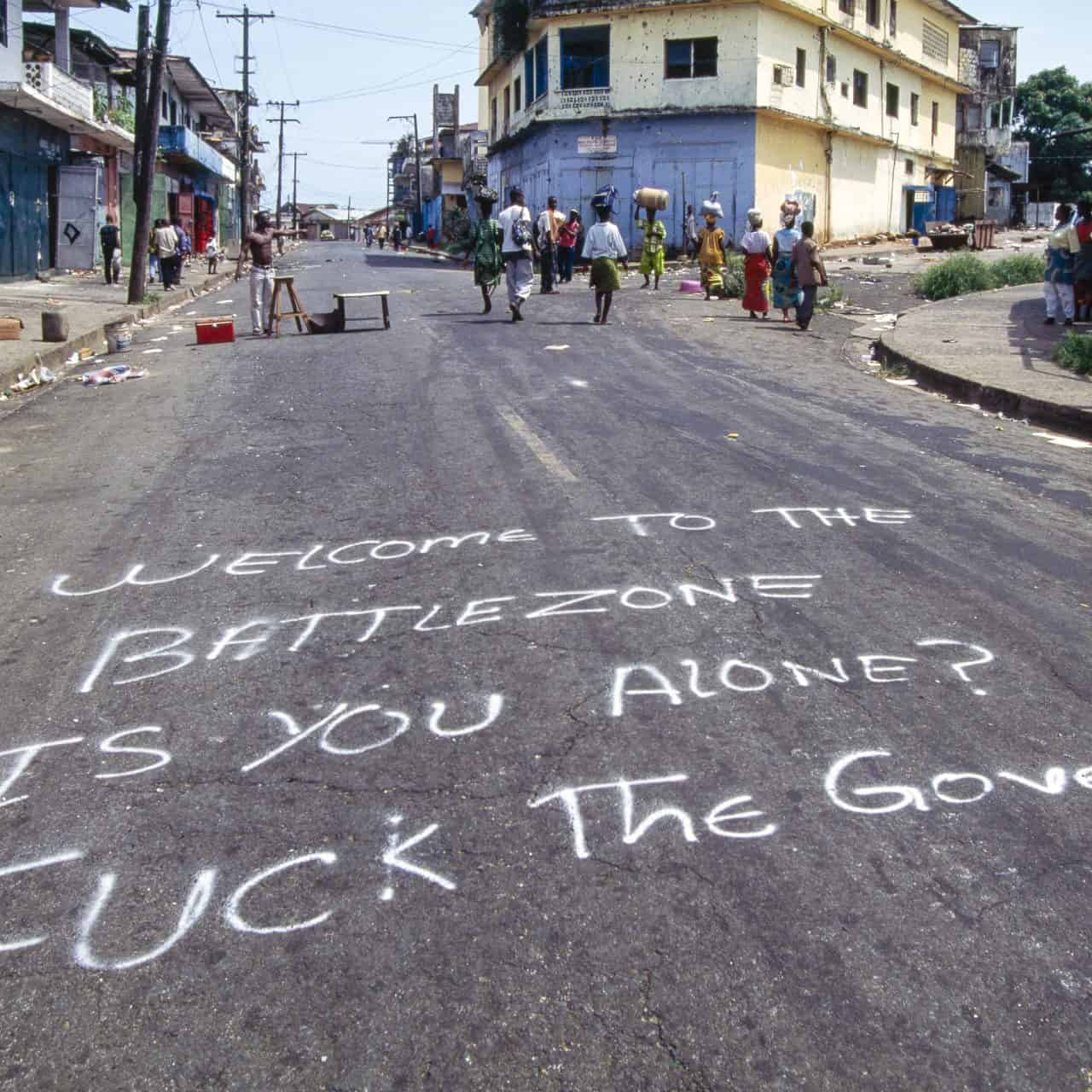

For large stretches of the first Liberian Civil War (1989 – 1996) most of the country was under control of the NPFL (National Patriotic Front of Liberia), led by Charles Taylor. The faction is responsible for a very large number of international crimes, including sexual slavery, mass murders and conscription of child soldiers. Over 60,000 human rights violations committed by the NPFL were formally recorded by the Liberian Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

According to the indictment, Thomas Woewiyu served as the faction’s spokesman and worked to justify its mission and objectives to high ranking foreign officials. Since 1972 Woewiyu had been living in the United States where is has legal permanent residency, occasionally returning to Liberia. On January 23, 2006 he made an application for United States citizenship by submitting an Immigration and Naturalization Service (“INS”) Form.

Woewiyu was accused of having lied in order to obtain citizenship, failing to disclose his association with the NPFL as well as the fact that he was connected to crimes committed by the NPFL.

Woewiyu faced trial starting on June 11, 2018. He was convicted of 11 out of 16 counts on July 3, 2018. He faced up to 110 years in prison.

On April 12, 2020, Woewiyu died of COVID-19 after a week of treatment at the Bryn Mawr Hospital in Philadelphia, US. He was still awaiting sentencing.

Civitas Maxima monitored the trial in cooperation with Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP.

TRIAL DAY 1: JURY SELECTION

Trial officially began today in the federal prosecution of Jucontee Thomas Woewiyu, the former Minister of Defense for Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia (“NPFL”). The case is being tried in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, and will be heard in the James A. Byrne Courthouse in Philadelphia.

Woewiyu is accused in a 16-count criminal indictment of giving false information on his citizenship application, and of perjuring himself in related interviews, by not admitting his involvement with the NPFL. The prosecution alleges that, among other misleading statements, he lied about whether he ever advocated the overthrow of any government by force or violence; and about whether he ever persecuted anyone because of their race, religion, political opinion, or membership in a social group. To prove each of the immigration-related crimes, the prosecution will have to prove the underlying acts that Woewiyu allegedly lied about; for example, witnesses are expected to testify about his alleged group-based ethnic persecution of Krahns and Mandingos, and about his alleged opinion-based persecution of civilians whom the NPFL suspected of collaborating with its opponents.

Jury selection took place today. The prosecution and defense agreed to 12 jurors and four alternates out of the 75 potential jurors brought to court. The members of the jury will have the duty to hear the evidence presented throughout the case, and at the close of the trial they will decide if Woewiyu is guilty “beyond a reasonable doubt” on each of the 16 counts. The government prosecutors have the burden of proof, and are expected to call a number of witnesses – at least 12 of them traveling to Philadelphia from Liberia – to testify about Woewiyu’s alleged acts. The trial is expected to last approximately three weeks.

Federal Judge Anita B. Brody will preside over the trial. Judge Brody was nominated to the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania by President George H. W. Bush in 1991. She previously served as a Deputy Assistant State Attorney General in New York and a Judge of the Court of Common Pleas for Montgomery County in Pennsylvania.

There are two federal prosecutors trying the case, and two public defenders representing Woewiyu. Assistant U.S. Attorney Linwood C. Wright, Jr., is lead counsel for the prosecution, a role he also filled last year in the trial of Mohammed Jabbateh (a.k.a “Jungle Jabbah;” Civitas Maxima’s monitoring reports from that trial can be found here.) As in the Jabbateh case, he is joined by Nelson S. T. Thayer, Jr., an Assistant U.S. Attorney who previously served as a war crimes prosecutor with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, in The Hague. Woewiyu is being defended by Mark T. Wilson, Senior Trial Counsel at the Federal Community Defender Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, who has previously represented Guantanamo detainees; and Catherine Henry, a Senior Litigator with the Federal Community Defender Office, and a lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania Law School.

Trial will continue tomorrow with opening statements, followed by the testimony of the government’s first witnesses. Watch this space for daily updates throughout the trial.

TRIAL DAY 2: OPENING STATEMENTS; GOVERNMENT’S FIRST WITNESSES

Jury Instructions

The Thomas Woewiyu trial commenced in Philadelphia on Tuesday morning with Judge Anita B. Brody reminding the jurors of their sworn duty to base their ultimate decision about Woewiyu’s guilt on the evidence presented at the trial. “I play no part in finding the facts,” she said, telling the jury not to take into account anything she says or does during the trial, but instead to pay strict attention to the witnesses they hear and the documents they see over the next few weeks. She instructed the 12 jurors and the four alternates not to let sympathy, prejudice, or fear influence them, and told them not to concern themselves with any punishment that might occur if they find Woewiyu guilty. Their focus must be on the whole testimony of every witness, deciding on the truth of what each says.

Judge Brody reminded the jury that Woewiyu cannot be convicted based on any of the jury’s assumptions about him; they may only find him guilty if they are convinced of his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. The judge explained that a “reasonable doubt” is a “fair doubt based on logic, reason or experience,” that might arise from the evidence itself or from a lack of evidence. She reminded the jurors that at the close of trial, for them to find Woewiyu guilty of any or all of the 16 charges against him, the verdict must be unanimous on each charge.

Woewiyu has pled not guilty on each of the 16 fraud, false statement, and perjury charges the prosecution will seek to prove.

Prosecution Opening Statement

Assistant United States Attorney Nelson S. T. Thayer, Jr., delivered the opening statement for the prosecution, outlining the government’s case and previewing the evidence the government intends to present against Woewiyu. “This case is about lies,” he said, lies that Woewiyu told to obtain U.S. citizenship. Thayer told the jury that the evidence will show that while Woewiyu was under oath, he lied on official U.S. government forms, in particular his Citizenship Application Form N-400, and that he repeated those lies, again while under oath, in a subsequent interview with an Immigration Officer.

Thayer began by taking the jury step by step through each of the questions on the Citizenship Application that the government alleges Woewiyu answered by lying. The first such question on Form N-400 asked, “Have you ever been a member of or associated with any organization, association, fund, foundation, party, club, society, or similar group in the United States or in any other place?” Thayer displayed an extract from Woewiyu’s Form N-400, showing that Woewiyu answered by checking a box marked “No.” The next question Thayer read to the jury asked, “Have you ever advocated (either directly or indirectly) the overthrow of any government by force or violence?” Thayer again showed the jury an extract from Woewiyu’s Form N-400, showing that Woewiyu again answered no. The third such question Thayer read asked an applicant for citizenship, “Have you ever persecuted (either directly or indirectly) any person because of race, religion, national origin, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion?” Thayer again showed an extract from Woewiyu’s Application, and told the jury that the evidence will show Woewiyu answered no under penalty of perjury. The last part of the government’s case rests on a question about prior convictions; Woewiyu answered that he had never been convicted.

“Why did Thomas Woewiyu lie?” Thayer asked the jury. “What motive did he have to lie?” Thayer said that the evidence will show Woewiyu had “a powerful motive to lie,” trying to conceal that he was in fact a founding member of the National Patriotic Front for Liberia (“NPFL”), and that the NPFL started the First Liberian Civil War. Thayer stated that the evidence the prosecution presents to the jury will show Woewiyu in his role as a leader of the NPFL committing acts of persecution and human rights abuses, including the forced recruitment and use of child soldiers, and ordering the torture of bound and beaten prisoners. Woewiyu committed these acts not as a low-level soldier, Thayer said, but as a founder, the chief spokesperson, and the Minister of Defense of the NPFL. According to Thayer, in those roles Woewiyu promoted, endorsed, and promulgated NPFL policy, and in many ways “personified that policy,” particularly in his use of child soldiers.

Thayer acknowledged that the war in Liberia was thousands of miles away from Philadelphia and happened over 20 years ago, and that the jurors may ask themselves why they should care about what a man in his seventies wrote on a government form in 2006, and said to a government officer in 2009. He explained that the United States has a “vital interest” in ensuring that its immigration system works “to welcome those truly deserving of the rights historically offered to people all over the world.” He said that the citizenship process depends on truthful answers to questions that help Immigration Officials determine a candidate’s good moral character, and described how a candidate is interviewed after submitting a Citizenship Application. Thayer said that the immigration process was a “gatekeeping process,” and it required lots of form-filling in order for the government to gain “the most accurate, truthful, and complete picture” of the applicant that the government could. Thayer said that for a foreign-born person, U.S. citizenship is a privilege, not a right, and that the forms ensure that only those most deserving can obtain citizenship.

Thayer told the jury that they would hear evidence about Woewiyu’s immigration interview, which occurred in January 2009. He said that when the Immigration Officer went over Woewiyu’s forms with him in that interview, she pressed him about whether he truly belonged to no organizations. According to Thayer, Woewiyu acknowledged that he belonged to a union of Liberian associations in the United States, but did not disclose his role in the NPFL, according to Thayer. Thayer then showed the jury a photograph of Charles Taylor, with Woewiyu standing just behind him, and said that Charles Taylor was the only person more senior than Woewiyu in the NPFL. Thayer told the jury that they would hear Woewiyu’s words for themselves, accompanying evidence like the photograph, as in a 1994 press conference where he referred to himself as a founder of the NPFL, and in an affidavit given in a Dutch case in the 2000s.

Thayer told the jury, “You will hear from journalists, photographers, United States Department of State employees, diplomats, and ordinary Liberians who all knew Thomas Woewiyu was serving at the highest echelons of the NPFL.” He listed some of the journalists who will testify, including Elizabeth Blunt and Mark Huband. Thayer said that Mark Huband was captured by the NPFL, and taken in to the jungle to see Charles Taylor, and that while there Huband saw Woewiyu with Taylor, dressed in military fatigues, and sitting with an “AK-47 machine gun between his knees.” Thayer said that Woewiyu acted as a Minister of Defense by recruiting fighters, obtaining ammunition and supplies, delivering those to the fighters, visiting the fighters at the battlefront, and briefing the fighters. Thayer said that Woewiyu also acted as chief spokesperson, giving interviews on the radio and in-person. Thayer told the jury that Elizabeth Blunt performed many interviews with Woewiyu, who was the “acceptable face” of the NPFL, although the methods the NPFL used “were far from acceptable.” He explained that the Liberian witnesses who will testify come from different tribes and different parts of Liberia, but that the one thing they have in common is their “fateful contact” with Woewiyu.

Some of the witnesses are expected to testify to Woewiyu’s use of child soldiers, including as his personal bodyguards. Thayer told the jury that the child soldiers were used “like any other weapon of war” by the NPFL. Thayer told the jury that they were used like other weapons, and they were “used” meaning “abused and manipulated.” Many of the children were photographed with AK-47s that were bigger than they were. Thayer called the child soldiers “the tip of the spear, tools of terror for the bloody civil war.” He described how the children were put at checkpoints which became the hallmark of horror set up all along the roads of Liberia. Instead of a wooden gate, he said, the checkpoints were crossed by human intestines and had human skulls perched along the sides. “As you listen to the evidence, you must ask yourselves,” Thayer told the jury, “is it any wonder that Thomas Woewiyu didn’t write down the four central letters NPFL, and is it any wonder he couldn’t utter them during his citizenship interview?”

Thayer then described Woewiyu’s alleged involvement in an attempt to procure armaments, in a deal involving surface-to-air missiles, M16s, and ammunition.

Thayer completed the prosecution’s opening statement by giving the jurors a brief overview of the context of the First Liberian Civil War, describing how Americo-Liberians settled in Liberia and subjugated its people prior to the 1980 coup led by Samuel Doe, and how the NPFL responded to the Doe government. “You will hear from a number of witnesses who survived” the war, he said, “who will tell how the NPFL went about the business of war.”

Thayer ended by telling the jury that based on the evidence they will hear, “the lies Thomas Woewiyu told matter.”

Defense Opening Statement

The defense opening statement was presented by Catherine Henry, who began with a simple argument: that Woewiyu “never lied; he had no reason, no motive.” She told the jury that the only dispute in this trial is whether Woewiyu made false statements in four questions on his Citizenship Application and in his subsequent 15-minute immigration interview, and told the jury that the defense would show his answers were not lies.

Henry explained that the defense agrees that Woewiyu was in the NPFL, sometimes as a spokesperson and sometimes as the Minister of Defense. She characterized the NPFL’s goal as to oust Samuel Doe, an evil dictator, and told the jury that the defense does not dispute that some members of the NPFL committed violent acts in a brutal war. “We also agree there were child soldiers in the NPFL,” she said. Henry then asked the jury to consider why, if both sides agree, the government is bringing witnesses to Philadelphia to relive what happened to them and “to force you to listen to horror stories” when “there is nothing the court can do to fix what happened,” “much as we might want it to.” Henry suggested that the government’s strategy is to emotionally manipulate the jury, to distract them from the truth of the questions asked on Form N-400.

“There’s enough blame to go around,” Henry said, arguing that it was “a mess over there” and that Samuel Doe was a “bad man” whom Liberians around the world wanted to get rid of; that was why, she explained, Woewiyu in 1987 became part of a group to get rid of Doe. According to Henry, the United States had an interest in the subsequent conflict, because of the rubber plantations in Liberia, and played both sides, at times giving help to the NPFL. She told the jury that because “this was war, reasonable minds can differ and debate can go on,” but that the jury’s duty is not to pass judgement about what happened in the First Liberian Civil War, and only to pass judgement in the immigration fraud case.

Henry argued that the citizenship process is complicated and subjective, and told the jury that Form N-400 is now 20 pages long to clarify the “confusing” questions that existed when Woewiyu filled it out in 2006, when it was ten pages long. She told the jury that Woewiyu filled the form out with his attorney, who will appear as a defense witness, and that the attorney also accompanied Woewiyu to his immigration interview. Henry explained that Woewiyu then filled out a follow-up form, an N-14, that included more information about groups to which he belonged, including the AFL-CIO union, various church groups, and the NPFL. According to Henry, Woewiyu’s alleged perjury and immigration fraud cannot be taken in a vacuum as occurring on his Citizenship Application and in his interview, but must be considered in light of the subsequent information he gave. She called his Application, the Form N-400, “a living and breathing document.”

Henry described Woewiyu as an “open book” who came to the United States in 1969 on a student visa and who has since lived here legally, and argued to the jury that “our government knew who he was.” According to Henry, Woewiyu met with Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) agents as well as with immigration officials twice in his capacity as a spokesperson for the NPFL, long before his immigration interview. She described FBI agents reaching out to Woewiyu as part of an attempt to deport the Liberian national George Boley from the United States, saying that they put Woewiyu on a list to be called as a witness in that case.

Henry agreed with the prosecution that U.S. citizenship is “precious,” but argued that the government cannot say that Form N-400 would be the basis of a citizenship decision, because the government already knew about Woewiyu’s past. She pulled out a copy of Woewiyu’s “A-File,” a large thick file that the immigration officers had when he applied for citizenship, containing information like updates he made to his Legal Permanent Resident information. According to Henry, the government knew everything about Woewiyu, so they cannot now claim that he lied.

Henry argued that it is not criminal to misunderstand or differently interpret Form N-400, and reminded the jury that they can only find Woewiyu guilty if they believe he deliberately lied. According to Henry, during the immigration interview Woewiyu tried to answer the question about groups he belonged to, but when he reached into his briefcase for his resume to show the Immigration Officer his affiliations, she said the interview was only 15 minutes long and that they could reschedule. Henry told the jury that Woewiyu only had time to name an umbrella organization that included the NPFL and other Liberian associations.

Henry described Woewiyu’s replies to subsequent questions as based on his subjective interpretation, and not deliberate lies. She told the jury that Woewiyu did not consider Doe’s dictatorship a government, so he could not have answered “yes” to advocating its overthrow. She said that while political scientists may say that Doe had a form of government, that was not the case in Woewiyu’s mind. Similarly, she said that while the First Liberian Civil War was brutal, Woewiyu was not the one “laying hands on people,” he was a “press secretary” and “believed he was just fighting a war” to bring democracy, so he did not answer that he ever persecuted anyone. Furthermore, she said, because Woewiyu firmly believed that his aim was to help rid his country of a vicious dictator, he did not single anyone out based on race or ethnicity, and saw the acts carried out as “trying to defeat the enemy.” Lastly, Henry told the jury that Woewiyu never tried to hide the petty conflict with American police for which he was convicted; she said that although he answered “no” to the question on Form N-400, he described his conviction later in the same form.

Henry told the jury that the government did not dispute that the later-filed form, the N-14, was correct. Henry told the jury that the government had received all of Woewiyu’s information during the immigration application process, and so following the government’s adjudication and denial of Woewiyu’s application, the matter should be over. She said that instead, the government attorneys travelled to the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Liberia in order to create witness lists and build their case.

Henry then alleged that the United States cannot prosecute war crimes, saying the prosecutors are using immigration law to prosecute the war in Liberia here. She told the jury that Liberia has already had a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and that Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, “a former President and a Noble Peace Prize Winner,” herself decided that they should not be prosecuted.

Henry ended her statement by focusing on Woewiyu’s having answered these questions “to the best of his knowledge and ability;” it was with that understanding, she said, that he signed Form N-400.

Witness 1: William “Danny” Tinga

The prosecution’s first witness testified on Tuesday afternoon. William “Danny” Tinga told the court that he was not expected to be the first witness, but that a colleague’s injury occasioned the change in witness order. The witness described his career as a Dutch police investigator, and explained that through the range of cases he investigated, the common denominator was a complex international component.

Tinga was the coordinator and lead investigator in the Dutch police investigation of Gus Kouwenhoven, a Dutch national, for arms trafficking during the period of United Nations sanctions. Tinga described going to Liberia in 2004 with his fellow investigator Huig “Lewis” Bouter, and their interpreter Arien Zuijdwijk, to interview witnesses and build a case file on Kouwenhoven. The process they followed conformed to their typical procedure, which is based on the strictures necessary to admit police statements into Dutch courts. Interviews were conducted at the Mamba Point Hotel in Monrovia, with questions asked by the investigators in Dutch and translated into English by the sworn interpreter; English answers were then translated into Dutch and compiled into a Dutch statement which was read back to the witness in English. Any corrections would then be made. The witness identified a photo of the hotel room that was used as an office, and himself and his colleague Lewis in the photo.

Tinga testified that he did not remember conducting an interview with Woewiyu, although he did remember his name as an interviewee. Tinga told the court that if he signed anything showing he conducted such an interview, then he must have conducted it. When the prosecution showed Tinga a police report with his signature, describing an interview with Woewiyu, he said that because he signed it, he knows it must be an accurate and correct document of the interview, a word-for-word story of the witness. Tinga also identified a photograph of Kouwenhoven, the Dutch suspect, with Taylor.

On cross-examination, Tinga confirmed that Woewiyu’s interview was given voluntarily, as all such interviews were. He said that his own interview by United States prosecutors about Woewiyu took place in Amsterdam; on re-direct, he explained that it was more convenient for him to be interviewed in Amsterdam than the United States.

Witness 2: Arien Zuijdwijk

The prosecution’s second witness was Arien Zuijdwijk, the sworn interpreter and translator mentioned by the previous witness. She has worked with the Dutch National Police since 1985.

Zuijdwijk described the translation process always followed in police interviews, telling the court that the investigators’ questions were asked in Dutch, which she would translate into English for the witness, and then she would repeat the process in reverse. A witness’s Dutch answers were recorded in a written statement typed by one of the investigators; at the close of the interview, she would read it back to the witness in English, and any corrections would be made as necessary. All parties were then asked to sign the Dutch statement.

Zuijdwijk identified the official police report recounting the statement of Woewiyu, as she signed it at the time it was given as a true representation of his words; the report was then read aloud in English by the prosecution, while Zuijdwijk followed the Dutch version of the statement and noted any discrepancies. In the statement, Woewiyu called himself “the co-founder of the NPFL, together with Charles Taylor.” He described meeting Gus Kouwenhoven in Sierra Leone in June 1990 at a peace conference, at which Kouwenhoven asked if Woewiyu had received the $150,000 Kouwenhoven had sent him via Linco. In the statement, Woewiyu said he used part of that money to purchase arms, and described Kouwenhoven as a friend of Doe who also helped Doe’s enemies. He said that later, although the Labor Minister in the late 1990s, he still had a “fair amount of influence in military affairs,” including with the NPFL.

The statement described Woewiyu’s connections to Kouwenhoven in the late 1990s, explaining that Kouwenhoven set up a logging company called OTC, and that he brought in truck drivers and cleaners from outside of Liberia. Because this was illegal, Woewiyu had to make exceptions to the law. Although Kouwenhoven was unhappy, Charles Taylor told him to do what Woewiyu said. The statement also described Taylor giving large tracts of land to Kouwenhoven’s logging concerns, including land owned at the time by Woewiyu. The statement concludes with an assertion that Woewiyu did not want to sign it because it was in a language he did not understand, but that he would sign the English version.

Next, the prosecution showed Zuijdwijk a statement resulting from an interview done with Woewiyu by a Dutch investigative magistrate judge, and the English version of the statement attributed to Woewiyu was read aloud by the prosecution and checked by Zuijdwijk against the official Dutch record. In the interview, Woewiyu again described meeting Kouwenhoven in Sierra Leone, and said that Kouwenhoven sent the NPFL $150,000 because “he wanted to help” as he had business interests – wood-cutting and mining – in Nimba County “where the war was going on.” Half the money was taken, but half was used for arms. The interview also described an agreement between Woewiyu and Kouwenhoven that 15% of any logging profits were to go to the NPFL Ministry of Defense, and that Charles Taylor was aware of the agreement. According to the statement, Taylor gave over half the woodlands in Liberia to Kouwenhoven, including a piece of land owned by Woewiyu.

“How do I know this?” Woewiyu purportedly asked in the statement. “Because I was Minister of Labor at the time.” The statement went on to describe the same labor dispute as the 2004 statement made to Tinga, and adds that the laborers brought in from abroad and working in Bassa County were armed, carrying AK-47s. It called the OTC detail “actually a militia” that had “better arms than the army.” According to the statement, Woewiyu knew this “because I was the former Minister of Defense.” The statement continued, “Most of OTC’s employees were former fighters of mine.” OTC was called an extension of the fighting forces, who went to Buchanan or Grand Gedeh to fight. The statement asserted that Woewiyu never physically engaged in fighting, but issued orders given to fighters. It was affirmed and signed by Woewiyu.

On cross-examination, the witness read out an additional paragraph from the statement indicating Woewiyu said that the security personnel of his company in Buchanan were not armed.

Witness 3: James Fasuekoi

The third prosecution witness, the Liberian photojournalist James Fasuekoi, began his testimony toward the end of the day on Tuesday. He identified himself as a member of the Loma ethnic group, and described the geographic dispersal of some other groups in Liberia, including the predominance of Gio and Mano people over Mandingo people in Nimba County.

Fasuekoi was in Liberia when Samuel Doe came to power, and when the prosecution showed him a photo of Doe, Fasuekoi recognized it as one he himself had taken. He described Doe seizing power in 1980, assisted by 16 people from the army, and explained that Doe’s coup was in reaction to the brutal style by which Americo-Liberians had ruled Liberia for years, when the indigenous Liberians were marginalized.

Doe announced “that the time of the people had come;” President William Tolbert, who was Americo-Liberian, was assassinated. Fasuekoi testified that 13 of his cabinet government officials were arrested and taken to the beach in Monrovia and executed. Many citizens were in the area, and the witness himself went to the beach the same afternoon the executions happened. He recalled the executed were tied around their waists to electric polls, some with their heads opened because they were shot in the head.

Fasuekoi also recalled that when Samuel Doe first took over, many people jubilated and marched through the streets of Monrovia and paid homage to the new leaders; however, the jubilation did not last, because the new government had the same vices as the past government: corruption, abuses of power, and secret killings. The witness described the Doe government as “reborn” into the same abuses of power as before, including hurting perceived enemies. He explained that there was a general perception that Doe favored Krahns because Doe was a Krahn. He said that Mandingos also declared support for Doe when the war broke out, because he made a declaration that they were citizens.

Fasuekoi remembered the day in 1985 when General Quiwonkpa, who was Gio, led an attempted coup against Doe. The witness woke up to the radio playing the National Anthem, which could be either good or bad. The anthem was followed by a short speech saying Quiwonkpa had come to liberate the Liberian people from the hands of a tyrant. According to Fasuekoi, Quiwonkpa then moved his men around the city and seized members of Doe’s government, eventually taking to the barracks. The witness described Doe moving his “strong men” toward the barracks, taking control of the situation and arresting plotters in a house to house search. He recalled that Quiwonkpa was located in a makeshift building and killed after a brief firefight.

The witness told the court that Doe remained in power after the subsequent 1985 election, but that in his own view, the election was a fraud. As a journalist, Fasuekoi covered various events at which the international community was present with Doe; the diplomatic corps were always invited and were there. The United States had a strong presence, as did Great Britain and African countries; he thought Israel may also have had diplomats present.

Fasuekoi testified to the events of December 24, 1989, when the NPFL came across the Ivory Coast border and attacked the village of Buoto. He circled a village called Bluonto on a map for the court, and described how the war continued and spread over Nimba County and began to move toward Monrovia. He said that eventually he planned to escape the city, but by then the city was on fire.

The witness described rebels from the NPFL who came to his neighborhood. They wore tattered clothes, worn-out shoes, and were half-dressed in military uniforms. “Some wore wigs like ladies wear to beautify themselves, but dirty and ragged.” He recalled that they were “armed to the teeth,” carrying “all sorts of weapons,” and told the court that while he was not a military expert, the most popular weapons were a Berretta and an AK-47.

Fasuekoi testified about living near the National Oil Refinery, and encountering the NPFL in his own neighborhood. At that time, one of his neighbors, a friend, was a Krahn. Some Krahns were going to the barracks for uniforms and guns to protect themselves, but Fasuekoi never saw his friend with a gun. Rebels came to the neighborhood, and on hearing gunfire, everyone ran into their houses, and on coming out, Fasuekoi saw his Krahn neighbor dead. The NPFL had tied him “duck fa tabae,” elbow to elbow in the back, “and the NPFL told us at gunpoint to bury him.” The witness, when shown a photograph, said that it showed what he meant by “duck fa tabae.” The photograph was also shown to the jury, and the witness said that though it was never done to him, he has heard from others that it was very painful.

Fasuekoi testified that his friend had gunshot wounds all over his body, and the rebels were saying nasty things about his background, like calling him a “Krahn dog” when telling Fasuekoi and other neighbors to bury him. Fasuekoi explained to the court that “I was troubled with the condition his body was in, and asked if we could loosen his hands.” An NPFL rebel told him, “Next time, you go in the grave with him.” The witness and other neighbors had dug a hole by then; he remembered there were many ants, so they could not stay in place while digging, and had to brush their knees.

The witness came out of the witness box and demonstrated for the jury how his friend was tied, and lay on the courtroom floor to show how his friend was thrown in the grave, face-down. He said that told his fellow neighbors, “Let’s turn him around, face up,” because it is normal to have the dead facing towards the heavens. The NPFL rebel warned Fasuekoi again, and he did not say anything else until they pushed dirt over his friend. This happened in late July, toward August, of 1990.

At this time, the witness said, he was talking to the uncle he was living with about needing to move. He described his uncle procrastinating and saying that Taylor was already in the city so everything would be over in a matter of days.

Fasuekoi testified that around August 2 or 3, the NPFL set a siege around his neighborhood, because there were still some army men around the National Oil Refinery. He said that the army men told him and his neighbors to go in their houses, because they knew the NPFL was coming. The battle was very close to his house, and he could hear guns and grenades. He thought he would die. The witness hid under a bed with his foster-brother, and they fought over a Bible.

After an hour, when it was safe to come out, his uncle agreed that they needed to leave; there were 13-16 household family members to get out. They left and headed in the direction of the University of Liberia campus outside of Monrovia. Fasuekoi recalled that they left the family dog behind. There was not enough food to feed dogs, and dogs were already feeding on bloody human bodies in the streets.

The government’s third witness will continue testifying on Wednesday morning.

TRIAL DAY 3: THE GOVERNMENT’S CASE CONTINUES

When trial resumed on Wednesday morning, one of the jurors was not present. That juror was recused and replaced with an alternate.

Witness 3: James Fasuekoi, Continued

The government’s third witness, the Liberian photojournalist James Fasuekoi, continued testifying on Wednesday morning.

Fasuekoi testified that prior to the 1985 attempted coup by General Quiwonkpa, there was the earlier “Nimba Raid” in 1983. He stated that the raid was carried out by disgruntled citizens in Nimba – including Gios and Manos – who “rampaged,” targeting those who had animosity against them. These citizens “ran up” supporters of President Samuel Doe, including those in authority. Eventually some people were killed; according to Fasuekoi, it was “something like a mutiny.” The witness said that in 1985, following General Quiwonkpa’s failed insurrection, some of Doe’s army came into Nimba County and “ran up” Gios and Manos in retaliation.

Fasuekoi stated that Charles Taylor was the leader of the NPFL, and he recognized a photograph he had taken of Taylor.

Fasuekoi told the jury that the area where he lived and where his friend was killed – a death he testified about yesterday – was controlled by the Doe government forces until rebel forces came in. The witness’s family fled, he continued, after the massacre in Lofa County, and after they saw some of their neighbors killed, and the bodies in the street and dogs eating them; the family decided that they should move to the Roberts International Airport near Harbel, where the United States had a presence.

Fasuekoi testified that his family encountered many “checkpoints” during their journey. The witness explained that a “checkpoint” is a roadblock set up by those fighting the war, as a way to search for enemies. According to Fasuekoi, checkpoints were manned by both adults and child soldiers; the children’s ages varied somewhere between seven and 15. Fasuekoi asserted that he saw child soldiers with his own eyes many times.

The first checkpoint Fasuekoi and his family came to when they fled was in Johnsonville. Fasuekoi saw a child soldier armed with a bayonet with the rebels. The witness confirmed that this was an NPFL checkpoint, and said that he ran into countless NPFL checkpoints along the way. He stated that child soldiers were armed just as adult soldiers were.

The witness recognized two photographs, each one of a different young boy holding a rifle, as photographs he had taken. He identified both children as part of the NPFL faction. He confirmed that the photographs were an accurate depiction of how the children looked at the time.

Fasuekoi testified that his family arrived at the Johnsonville checkpoint in the early morning, and said that it must have been around 7:00, because they had talked to the “people running back and forth,” and had heard that the best time to enter the rebel territory was early morning. This was allegedly the time it was possible to move quickly and without much harassment.

The witness told the court that the child soldier he encountered at the Johnsonville checkpoint had a knife and a single-barrel firearm. The child halted the family and began checking their luggage; Fasuekoi had an old suitcase of clothes. Fasuekoi said that when the child got to Fasuekoi’s uncle’s luggage, an adult rebel said he saw something like a shell casing from a gun, and demanded the uncle tell him “the truth.” The little boy was still going over what was in the suitcases, laying things left to right. Fasuekoi thinks maybe the shell was laid there by the rebel; he remembers the adult rebel saying, “Tell the truth or I kill all of you.”

Fasuekoi testified that his uncle was trembling, and that his uncle told the adult rebel that he only had a pistol before the war for his own protection. According to Fasuekoi, the man replied, “I’m gonna kill all of you.” The witness was aware, as he lived with his uncle, that his uncle had a firearm back in the ’70s.

“We began begging,” Fasuekoi testified, and described his neighbors, who were also fleeing, asking the adult rebel to let them go. Instead, Fasuekoi continued, “he told us to form a line beside a stream” where Fasuekoi had heard “they executed people.”

The witness described how through a single look, he and his foster brother understood that they needed to “make a move” to survive. Fasuekoi testified that they could communicate by a look or a movement, which they learned in the Poro society, so they did not have to say anything aloud. He told the jury that a Poro society is an African society, something like a university for men to become full citizens. The witness stepped out of the witness box to demonstrate the look, and showed how he took a step, and his foster brother moved closer to the adult rebel, who noticed something was going to happen. They were determined to seize his weapon, because he was alone at the checkpoint with the child soldier.

Fasuekoi said that the rebel pointed at him and his foster brother and ordered them to halt. Fasuekoi alleged that the rebel said “You guys stand here,” and put them at the front of the line by the stream and told them, “I’ll kill you first.”

The witness told the jury that his neighbors began begging the rebels to spare their lives, and the adult rebel told the neighbors to take the family’s oil and rice, saying, “Take it away. I’m going to kill them.” According to Fasuekoi, his neighbors were unhappy but some took the oil and rice, because there was no food. He said that with the neighbors’ begging, “something clicked,” because the rebel said, “OK, I forgive you, it’s still early.” It was probably 7:30 by then. The neighbors gave them back some rice, and the family continued from there.

Fasuekoi testified that all along the road they saw the dead, and that some were “good looking, like they were former government officials.” He told the jury that he would never forget a man he saw by the roadside, with flies all over them.

The family continued to the Fendell Campus of the University of Liberia outside Monrovia. Fasuekoi testified that when they arrived on the outskirts, they ran into thousands of people waiting in lines to be interviewed by rebels. He alleged that the rebels had a makeshift administration that was “acting like Immigration,” checking everyone’s tribe and taking some people away. He explained that everyone had to speak in their mother’s tongue to say what tribe they were from, and that the checkpoint guards had a way to tell if people were lying. For example, if you said you were Loma, they had someone there to talk to you and to see if you were genuinely Loma. Fasuekoi said that the person who talked to him and his family was “a mulatto lady.” He described this checkpoint as “the most fearful checkpoint we’d come to.”

Fasuekoi said it took two to three hours before the point where they were interviewed. He said it was “chaotic,” and that the checkpoint was controlled by the NPFL, including heavily armed child soldiers and adults of all ages carrying weapons and marching and staring at the civilians critically. He explained that if somebody was passing by, you tried not to look at their faces; that was the wrong thing to do because “you might look guilty or like a member of the wrong tribe.” Fasuekoi alleged that when civilians were asked which tribe they belonged to, they were either set free or “taken out somewhere else.”

Fasuekoi told the jury that Liberia has 16 distinct regional groups, none of which can hide from the others, although he knows Krahn women who survived because they passed as Bassa during the war. He said that the different groups or tribes understand each other’s languages,; for example, the Gios and Manos live with Mandingos, so they speak each other’s dialects. He said that people were able to detect if anyone at the checkpoint lied, because they had interviewers who understood each tribe’s language.

Fasuekoi alleged that people who were accused of being Krahn or Mandingo were pulled out and taken away from the line, although the crowd was too big to see where they were taken. He confirmed that they were not executed right before his eyes.

In line, people told each other how to say hello in other dialects. People who were just passing through, not in the line, described questions those waiting might be asked: “Who are you? Where are you from?” Fasuekoi’s family used a song to teach the children with them words in other dialects.

Fasuekoi described how interviewers would determine if someone was in the army by checking for boot marks on their legs. He said that for those in the army, it was a regulation to wear boots with socks, so soldiers all had marks that guards were checking for.

Fasuekoi testified that his family “made it through the checkpoint.” He explained that there were so many rebel troops that it was not a mounted checkpoint, but instead groups of heavily armed men were lined up. At other times he saw checkpoints with a semblance of normalcy, with rope across the road and men and women guards.

Fasuekoi testified that his family entered the campus, his school, and stayed there a few weeks. Close to August 24, he said, they heard an announcement that tension was growing because ECOMOG was arriving. He explained that ECOMOG were West African peacekeepers comprised of ECOWAS nations, who sent troops in to stop the war. He said there was news they would be landing in a couple of days, and he noticed the NPFL troops becoming agitated. The NPFL also sent more reinforcements.

“We were coerced to demonstrate against ECOMOG,” Fasuekoi said. He alleged that NPFL soldiers came to the dormitories to round up civilians staying there, and if the civilians did not come out, they would be shot. He described how thousands of people marched, denouncing ECOMOG, chanting, “We don’t want ECOMOG, we don’t want ECOMOG.” The next thing he saw was an army of news crews, television reporters, and photographers. Fasuekoi testified that old pickup trucks began arriving, with skeletons and skulls tied to them. He explained that most of the civilians were themselves just “skeleton bodies,” because there was no food. He said that the reporters were foreign news crews, who filmed the march.

Fasuekoi described living in an old science building with thousands of other people. He said that according to aid workers, there were 250 thousand people on the campus. He called the conditions “horrible,” saying he slept on a bare floor only after his family could secure a place inside. Before that, he said, they slept on doorsteps; when rain would wake his family up, they would sit against walls. After a couple of days outside, his family talked to other families leaving for Buchanan or Nimba, and negotiated for their inside place; Fasuekoi specifically remembers placing their mats and blankets there, as “those things were hard to get.” The witness recognized a photograph of himself at the science building, and one at the spot where he slept, on Concrete Slab #9.

The witness laughed when asked if there were schools for the displaced kids at the campus, and asked if the government lawyer was making a joke. He testified that there were thousands of children at the campus but no schools and no healthcare. Fasuekoi described his old neighborhood of Gardnersville in contrast: before the family fled, there were schools, and a hospital run by the government where children were delivered. There was law enforcement, he said, and basic services; when he was in the science building, there was nothing.

The family was getting scared, Fasuekoi said, and he observed lots of killing by the rebels in control. He described bodies thrown on the outskirts of the campus, many of them half buried. He told the jury about one time he had eaten something and had a runny stomach; he ran outside and sat down on something, and when he turned to his left he saw the grave of a person who was half buried. He said she must have been a lady because he remembers her colorful clothing. He gestured at his ankles to demonstrate for the jury how the body was tied up.

Fasuekoi testified that his family heard about an NPFL commander called Isaac Musa in control of an area, and that the family tried to get there. The witness identified a photograph of Musa; Fasuekoi himself took the picture during the second year of the war.

Fasuekoi remembered that on the university campus, teachers who were also refugees from ECOMOG countries were held hostage. He described Guinea, Ghana, and Sierra Leone as countries who contributed soldiers to ECOMOG, and alleged that teachers of those and other ECOMOG nations were kept out of sight in a building on campus. He himself did not see them, but he saw the building whenever he had to pass through the checkpoint to go find food.

Fasuekoi testified about a checkpoint his family encountered at Careysburg, on their way to Musa’s territory. He said the checkpoint was dangerous because there were two in almost exactly the same place.

Another checkpoint the witness recalled was one he passed before the Careysburg checkpoint; it was where a company of soldiers had been stationed, near a factory. Fasuekoi explained that his foster brother used to be a security guard at a warehouse there; someone at the checkpoint saw his security guard uniform in his luggage, and began to interview him, so the family started getting scared. Fasuekoi said that another rebel started checking Fasuekoi’s photo album, and saw a picture of him with George Weah – now the president of Liberia – and everyone stopped and asked how Fasuekoi met him. The checkpoint guards wanted to know if Fasuekoi would give them the picture. In the background he could see the guy investigating his brother, so he said “Of course.” The witness testified that he believed his brother was spared because of the photograph.

According to Fasuekoi, the family later came to the checkpoint at Careysburg with the powerful double gate. He testified that the rebel commander present said the family had violated Charles Taylor’s order by traveling on August 24, when ECOMOG was landing. The witness said that the commander demanded to know what the other checkpoints were doing. Fasuekoi testified he was traveling with 18 members of his distant family at this time, and all of them were detained at the checkpoint. He said they had left his uncle, who wanted to go to his wife’s house, not a strange place where he knew no one.

The witness alleged that the Careysburg checkpoint had several armed NPFL soldiers sitting and investigating people; these investigators were all adults. There were not many child soldiers there, but the witness said he sometimes saw 15-year-olds.

“There were two beautiful ladies in our team,” Fasuekoi told the jury, “and the rebel commander was aiming at having relations with one,” who was light-skinned. Fasuekoi testified that the commander “saw this distant cousin of ours and grounded us right there.”

Fasuekoi described how two women in the camp, rebel ladies who were there working as cooks, befriended himself and his foster brother. The women gave them food, and Fasuekoi wondered if his sisters in his village could be armed like them. According to the witness, the women told the brothers to “watch out at night” because “things happened;” they warned the brothers to use all their muscle and might not to step outside if told to do so, because “if you do, you disappear forever.”

Fasuekoi said that the brothers shared this warning with their group, which had many strong men in it. The men slept in an open area, but the rebels took Fasuekoi’s sisters on the other side of the building to spend the night. Fasuekoi explained that by “sisters” he might mean “distant cousins.” When soldiers came for the men, he said, the soldiers kicked them with boots and slapped them, and if they tried to drag the men out, the men used their last strength to lock onto something. Fasuekoi and his family locked arms and did not let the soldiers drag them outside to man the checkpoint, although the NPFL soldiers allegedly kept kicking them and saying “Man up,” and “This is war.” Fasuekoi described crying like a baby and his family saying, “We are not soldiers.” This noise disturbed other rebels, so after a while the soldiers would leave; this happened twice a night.

Fasuekoi testified that he stayed with his family there for close to two weeks, and that each day they were not allowed to go anywhere, and could only sit quietly by the checkpoint while some of the NPFL soldiers went on ambushes or on patrol. He remembered one soldier looking at him and touching his muscles, asking, “When you were in Monrovia, were you a soldier?” Fasuekoi told the jury that he showed the man his photojournalist I.D. and answered that he wanted nothing to do with the military, that he was a student at the University of Liberia, and that if the soldier wanted to kill him, he should go ahead. After that, the man left him alone.

Fasuekoi testified that the rebel commander of the Careysburg checkpoint was probably a Gio or a Mano from Nimba, and that he wanted one person from every group that passed through. “One had to disappear.” Fasuekoi said that they “either took one of the girls, or one of us.” He told the courtroom that one of his sisters volunteered to be the sacrificial victim, and turned herself over to the rebels so that her family could go. One night she and the other sister came to the men and told them that the rebel commander wanted that other sister, but she was married and had a jealous husband. The women had convinced the commander to therefore let the married sister go. The sister who would stay had a little two-year-old boy and the family discussed whether he should go or stay. Fasuekoi described the boy’s mother saying she would be lonely if the family took him when they left, so he stayed with her at the checkpoint.

Fasuekoi said that when the family was through the second of the two Careysburg checkpoints, a stone’s throw from the first, he saw a photographer he knew, and tried to avoid him. The photographer allegedly asked Fasuekoi’s foster brother why Fasuekoi was avoiding him, and Fasuekoi told the court that he was afraid because most of the men they knew from that side “could sell us out.”

Fasuekoi testified that there was still chaos going on because of the ECOMOG landing, so when the family heard they would not be allowed into the Firestone International Airport, they went to the Voice of America transmitter site. He said they only stayed there a couple of days, asking people for guidance to avoid rebel checkpoints.

Next, Fasuekoi said, he and his brother went to a village along the train tracks and stayed there a month. Their plan was to get back to Monrovia because they thought the areas controlled by ECOMOG would be safest, but according to Fasuekoi, “it wasn’t easy.” He described how the NPFL moved into the village and arrested the brothers as people not from the area around the village.

Fasuekoi said that he arrived back in Monrovia around Christmas season 1990, sometime in December. He said he resumed his work as a photographer, although he did not start right away, because family members were missing. After six months of the new independent paper The Inquirer begging him to take a job with them, he went to work for them as a photo editor and a frontline correspondent, and they began sending him out.

The witness identified a photograph he took of Thomas Woewiyu in 1991, at the opening of the highway from Monrovia to Taylor’s “Greater Liberia.” The witness described Woewiyu as the NPFL spokesperson and Defense Minister. Fasuekoi explained that by 1991 the war was in its second year, although there was an interim government in place. He said that the NPFL was fighting ECOMOG, and described the capital as cut off from the rest of the country that the rebels occupied. Anyone sneaking into rebel territory was interrogated and suspected of being a spy. “You could be killed for no reason,” Fasuekoi said.

According to the witness, it was for these reasons that when the NPFL decided to open the road, they had a grand event. He said Woewiyu led the half hour ceremony. The witness’s photograph of Isaac Musa was also taken at this time.

Fasuekoi testified that when the road was open, many people came to Monrovia from Greater Liberia. He said people were eager to enter the city, and he personally observed many coming in who were fleeing from the NPFL. There were thousands of people, and the witness recognized a photograph of the crowd he took that day.

The witness said the road was temporary; all of a sudden, the road was shut down, and the only people let in or out occasionally were groups like a football team. From what the witness saw that day, after people entered Monrovia, many did not go back. Personally, he knows people who used that day to enter Monrovia.

The witness recalled that in October of 1992, Monrovia was attacked by the NPFL in a heavy offensive called “Operation Octopus.” The witness remembered heavy artillery shelling close to buildings civilians resided in; he was still in Monrovia himself at the time, and said the city was in chaos. Fasuekoi said it was difficult to establish a clear motive for the operation, but because the objective was to seize Monrovia, the NPFL would fight ECOMOG or anyone living in Monrovia who supported the government.

Fasuekoi testified that he lived close to the airport in Sinkor and that there was a lot of fire directed at the airport. He said the rebels came close to seizing it. He described being unable to sleep, standing all night in the basement with kids. Sometimes Senegalese ECOMOG soldiers would come to take the people in the basement away from the heavy fire; he described being taken to the military base and being kept there until he was allowed to go home. He said the shelling happened between midnight and somewhere around four, five, or six in the morning. This fight, he said, lasted from November onward through December; he was still a journalist on the front lines during this time.

The witness was shown a photograph and identified it as one he took of leaders of the warring factions in Liberia. He could not pinpoint when it was taken, but testified that it must have been before Taylor joined the national unity government in Monrovia in 1995. The witness identified a number of people in the photograph, and their factions: Roosevelt Johnson, the founder of ULIMO, and after its split a member of ULIMO-J, which was predominantly Krahn; Francois Massaquoi, leader of the Lofa Defense Force in Monrovia; the leader of the remnants of the national army; Dr. George Boley, of the Liberia Peace Council rebel group; and Woewiyu. The witness was asked to point to Woewiyu, and he stood up in the witness box and identified the defendant in the courtroom. He described Woewiyu’s position when the photograph was taken as the leader of the NPFL-CRC, with “CRC” meaning “Central Revolutionary Committee,” a warring faction that fought against the NPFL as well.

The witness identified a photograph of NPFL rebel forces he took. The photograph shows men and children in a variety of clothes, not formal military uniforms. Fasuekoi said they were getting ready to go to the front lines and fight; he knew this because he was there in the war zone with them.

Fasuekoi also identified a photograph he shot at an airport in Monrovia when ECOMOG held a big press conference. The photograph shows young children, who were presented as prisoners of war who were captured at the front lines. The witness testified that ECOMOG did not use child soldiers, and he never saw any child soldiers with the national army.

On cross examination by the defense, the witness acknowledged that his photograph of the leaders of warring factions does not show Charles Taylor, and that none of the men in the photograph represented the NPFL at the time it was taken. He described taking the photo while covering a forum in Monrovia for the warring factions, and explained that the Armed Forces of Liberia first fought the NPFL, and then eventually joined a coalition of five rebel factions; the NPFL was the coalition’s rival. The witness acknowledged that, thus, at one time Woewiyu was part of a coalition rivalling the NPFL. The witness also acknowledged that his photographs of the two individual child soldiers, each holding a rifle, were not taken at a checkpoint.

Asked about the first checkpoint he went through, in Johnsonville, the witness said he had every reason to believe he would be killed if he did not stand in line with his family. “It was no joke,” he said. “Had you been there, you would see.” Fasuekoi credited divine intervention for his family’s escape, and the family’s hours of praying before leaving Monrovia. “For what he was charging my uncle for,” Fasuekoi said, “that one bullet shell was enough to kill everyone at that time.” He said that “some of us” wondered if the rebels were trained about whom to target.

Asked about the checkpoint where he gave away his photograph of George Weah, Fasuekoi explained that Weah is one of the best African football players in recent times. He said that the rebels taking the photograph was them paying homage to Weah, and described how sometimes the rebels laid down their weapons during international matches, and everyone watched them before the rebels ran back to the bush.

The witness stated that he did not remember if the road from Monrovia to Greater Liberia was opened during a truce between the NPFL and ECOMOG. He acknowledged his photograph of General Musa also shows the Nigerian commander of the ECOMOG forces, and that the picture was taken at the celebration of the road’s opening.

During a brief re-direct, Fasuekoi testified that there were lots of reasons someone could be killed at a checkpoint, including ethnicity. He also said that if there was a truce between the NPFL and ECOMOG for the opening of the road, the truce did not last.

Stipulations

Before the government presented more witnesses, Assistant United States Attorney Nelson S. T. Thayer, Jr., addressed the jury and explained that the prosecution and defense counsel had agreed to certain facts the jury should consider as evidence. He then read a list of these stipulated facts to the jury, as follows.

Before and during the First Liberian Civil War, five white female humanitarian aid workers lived in a house in a compound in Gardnersville. In October of 1992, two of them were killed in a car along with ECOMOG soldiers.

Approximately two days later, the NPFL entered their compound and ordered everyone out of the house. One of the three women remaining was shot and wounded almost immediately upon exiting, and was followed outside by the other two. The NPFL commander known as “Mosquito” ordered these three white women separated from everyone else in the compound. They were taken near a wall and accused of being American and of working with ECOMOG. “Mosquito” ordered these three women shot dead with an automatic weapon.

Witness 4: James K. Bishop

The next prosecution witness to be called was James K. Bishop, former United States Ambassador to Liberia. He described himself as a “career U.S. Foreign Service Officer,” who spent 34 active years in the Foreign Service, and who then spent 15 years working on international disaster response for The Interaction, a coalition that worked with the International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC), the United Nations, and other non-governmental organizations. He is now at the State Department on a part-time basis. The witness described his education, and how after 10 years specializing in African affairs as a Foreign Service Officer, he earned a related Master’s degree at Johns Hopkins University.

Bishop testified that after many years of service, he was appointed to several high-level positions. In 1979 he was appointed Ambassador to Niger, and in 1981 worked at the African Bureau of the State Department. In 1987, he was appointed Ambassador to Liberia. Subsequently, he served in Somalia until the U.S. embassy was evacuated in 1990. He told the jury that a typical ambassador serves for two to three years in a given position, and described the duties of an ambassador as representing the interests of the United States abroad, serving as Chief of Mission at an embassy, and working on programs of assistance from the military to the Peace Corps.

Bishop outlined for the jury the procedure of being appointed an ambassador. He said that a prospective ambassador is nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate, which involves a hearing by a Senate subcommittee. The host government is notified and asked if they acquiesce to the appointment, and there is a formal way by which they indicate their answer. Bishop said the notification of the host government occurs via the appropriate U.S. embassy, which informs the host country’s Foreign Minister of the nomination.

Bishop testified that when an ambassador arrives, a colleague and someone from the host nation greet the nominee; this happened to him in Liberia. He described being met at the airport by someone from the Liberian government, and told the jury that he then met with the Foreign Minister so the Minister could arrange a meeting with President Doe so Bishop could present his credentials at a ceremony. Bishop was accompanied to his meeting with Doe by other senior staff of the U.S. embassy in Monrovia, he said. He testified that among the people with him were military officers in uniform. Bishop said that at the ceremony he announced to Doe who he was and what he was doing, and although he cannot remember his own exact words, he knew he said “something nice about American/Liberian relations.” He remembered Doe made a gracious response.

Bishop testified that he met with Doe on many subsequent occasions in person, and sometimes on the phone. He stated that sometimes they discussed the question of Liberia’s support for the U.S. in international fora like the United Nations, and sometimes they discussed aid programs; often they discussed problems Bishop had in dealing with Doe’s government, given a growing sense of corruption that was making it difficult to do his job. Bishop also remembered some lighter conversation topics, like visiting American V.I.P.s, and Doe telling Bishop about soccer and Bishop telling Doe about squash. Bishop remembered that among the American V.I.P.s who visited were members of Congress, the head of the C.I.A., and military officers who were in Liberia to help with military assistance programs.

Bishop arrived in Monrovia on April 12, 1987, which he said was “unfortunate” as that was the date of the 1980 coup through which Doe took power. Bishop recalled that at the time he arrived, the U.S. embassy was on Mamba Point on the sea front in Monrovia.

Bishop testified that he first met Doe in Washington, D.C., when Doe went there to visit President Ronald Reagan. Bishop said that he accompanied Secretary of State George Shultz to a meeting with Doe at a hotel. The witness identified a photograph of Reagan and Doe together and said it was a fair likeness of both of them at that time; he was in Reagan’s office fairly often accompanying foreign ambassadors, and could speak to Doe’s likeness because his meeting with Doe at the hotel was the day after the picture was taken. Bishop further testified that it would be usual for Doe to meet with the Secretary of Defense on such a visit, due to military agreements between the U.S. and Liberia. The witness identified Doe and then-Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger together in a photograph.

Bishop testified that he observed through his work that the government in Liberia had a “structure like the United States,” with separate branches and structures at the county level. He named ministries in the cabinet like the Ministries of Justice, Public Health, and Defense, and noted that the U.S. often assisted with their programs. He described the Liberian higher education system of two universities, and said that the public of the two had two campuses, including one outside Monrovia about 10 miles away. He described the public health system of Liberia, including John F. Kennedy Hospital, a “tertiary” hospital built with U.S. funds; private hospitals, including the one on the Firestone plantation; and Phebe Hospital in Gbarnga.

Bishop told the jury about taking his wife and two daughters on a road trip from Monrovia to Abidjan in Ivory Coast on December 26, 1989. He said that they drove up through the rainforest and crossed Nimba County, where the border guards made a fuss about the Ambassador and served them all Coca-Cola. Bishop said that the family spent the night in an Ivory Coast town called Man, and that when they arrived in Abidjan, his colleagues were in a state of alarm because on the radio they heard people announce an invasion in the same area where Bishop was. He stated that he made arrangements to fly back to Monrovia, where he found the city in a state of alarm.

Bishop testified that he had no contact with the NPFL while on the ground in Monrovia. He told the jury that his three-year term as the Ambassador to Liberia was coming to an end in March 1990, and there was someone primed to replace him. There had been no ambassador in Mogadishu in a year, and the State Department wanted to send him there as Ambassador to Somalia.

Bishop stated that before he left Monrovia, he saw that radios were made available to the NPFL, and assigned a Foreign Service Officer in Man to monitor them, because Bishop was concerned for the 5000 Americans in Liberia. According to Bishop, many were African-Americans “who were physically indistinct” from Liberians and thus likely to get caught up in the fighting. He testified that his goal in giving the NPFL radios was to “de-conflict,” to keep lines of communication open.

When Bishop left Monrovia in the last week of March or the beginning of April 1990, he learned he would not go straight to Mogadishu, but would instead go to Washington, D.C. to head a taskforce with the purpose of monitoring the Liberian situation and keeping the State Department informed. He said that once U.S. naval vessels were deployed to the water off Monrovia, coordinating with the Department of Defense was an additional duty. Bishop described how, as the war continued, part of the taskforce’s role was to encourage Americans to leave Liberia and to facilitate their leaving.

Bishop testified that the taskforce received a delegate from Monrovia, William Tubman, a former Foreign Minister and a representative of the Doe government, because “I thought to promote dialogue between the government and the opposition.” Bishop called Tubman “a prominent Liberian,” and said the taskforce wanted to serve as a bridge between the government and Charles Taylor, to encourage a conversation rather than a force of arms.

Bishop told the jury that before he left Monrovia as Ambassador, Doe responded to the incursion by sending troops to Nimba County. Bishop characterized the troops as “unprofessional,” and said they killed civilians, as did the NPFL. He described the war as “taking on a tribal cast.” He said that Doe was killing Gios and Manos, and that the NPFL was killing other sides. According to Bishop, he gave written instructions to aides who went to Nimba about what to do and what not to do, telling them to “report back.” He said that he met with Doe and counseled him to tell his troops to conduct themselves differently from the reports Bishop was hearing.

Discussing his subsequent taskforce in Washington, D.C., the witness told the jury that the talks he wanted to promote between the government and the opposition were called “proximity talks.” For such talks, the participants do not need to be in the same room; he described the participants as in nearby rooms, with State Department representatives “running back and forth” between them.

Bishop testified that he was informed Woewiyu would appear at these “proximity talks,” and said that Woewiyu claimed to be the Minister of Defense of the NPFL, and that Woewiyu said he had come to Washington, D.C. to talk. The witness said he thought he had two meetings with Woewiyu, but that it was a long time ago. He remembered several meetings with representatives of Taylor and the NPFL, talking about the possibility of talking through their grievances with the Doe government. The witness stated that these talks were in April 1990, but they were brief and did not work out, and the venue for future talks shifted to the U.S. embassy in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Bishop said his replacement, the new Ambassador to Liberia, went to Freetown to facilitate them.

Bishop said the NPFL objective was that it wanted the Doe regime gone, and was not clear on what would replace it, “and that’s what we’re trying to shape.” He reiterated that Woewiyu indicated he was the Minister of Defense “or some such title; he was in charge of the military.”

The witness examined a document that he recognized as a series of reports he prepared as chairman of the taskforce, for Herman J. Cohen, the Assistant Secretary of State for Africa, to whom he reported. Bishop said they were typical of the documents he would prepare for his State Department work.

Bishop recalled that the peace talks in Freetown after the “proximity talks” were not successful either, and that the White House did not want to be any further involved in the process by which “an escaped felon, as it was put to me” could become president of Liberia. He said that afterward, Liberian churches put together talks in Freetown that were also unsuccessful.

Bishop described the military situation at the time of the reports he made to Cohen. He said Doe and the Armed Forces of Liberia held the city of Monrovia, which he described as a “pretty big place” located on the coast. He said the NPFL had come down from Nimba by two routes, one via the railway line around the coast to Buchanan, and one via Gbarnga in the central part of the country. He noted that thousands had fled to the city from the country, and that the food situation was becoming increasingly critical. According to Bishop, the U.S. embassy had some emergency food delivered via the ICRC; food was put on trucks and “sent up there.”

Bishop testified that Doe’s Krahn tribal homeland was up the coast from Monrovia near the Ivory Coast border, and that Taylor’s forces were in between the Krahns in Monrovia and their homeland up-country. Bishop said that the idea was to keep the Sierra Leone road open, so that Doe supporters could escape and then reach their homeland by different entry points. He said that this was to “avoid a bloodbath,” and to avoid fighting in areas where there were refugees.

Examining a memorandum stating that Woewiyu admitted “excesses” occurred in Buchanan, the witness testified that he could not recall exactly what “excesses” these were. He said that both sides were savaging civilians and combatants, and that on the NPFL side, it was hard to tell between the two because NPFL fighters did not wear ordinary military uniforms.

The witness testified that he was personally acquainted with the five humanitarian aid workers whose deaths were described in the stipulated facts.

Bishop stated that from the NPFL, the only person he remembered meeting was Woewiyu, and said that they only met during the “proximity talks.”

On cross-examination, Bishop testified that he was aware Doe came to power by killing the prior president. He was also aware that 13 ministers died in the coup, tied to electric polls in front of a crowd. He was also aware that the only election Doe stood for was in 1985 after the attempted Quiwonkpa coup, and he said there was a considerable amount of fraud on all sides.

Bishop described his relationship with Doe as having “ups and downs, some very deep” over the three years Bishop dealt with him. Bishop stated that he considered Doe “ruthless and volatile.”

Bishop stated that after the incursion occurred, both forces behaved in a brutal manner. He said there was an “ethnic cast” to the conflict, with the army being Krahn and predominantly killing Gios and Manos. He said that prior to the incursion, there was not systematic killing of Gios and Manos by the army, and that to his knowledge, they were not targeted.

The witness testified that before the “proximity talks,” he did not have much background information about Woewiyu.

Bishop clarified that the “proximity talks” never took place, and that although Woewiyu came to Washington, D.C., the State Department could never get the two sides to talk, even with intermediaries. His recollection is that the two sides would not look at the grievances of the other party. He remembered Woewiyu wanted Doe gone, and the Doe government did not want to engage; the talks were to be about elections moving forward, and the Doe government was “sticking.” The witness described the Doe government as a “full-fledged government,” and said it had a legislature, although he did not remember the legislative calendar.

Bishop said that on December 26, 1989, he did not have any contact with fighting or combatant forces while driving through Nimba County. He stated that before he left Monrovia, there were no reports of an incursion.

The witness stated that he did not independently recall the context of a statement he made in a memorandum from June 29, 1990 about wanting to stall the credential presentation of the next Ambassador to Liberia, but agreed that it showed that at the time, Bishop thought it was not in the U.S. interest to support the Doe regime.

On a brief re-direct, Bishop agreed that the June 29, 1990 memorandum said the State Department “can” stall the new ambassador’s credential ceremony.

Witness 5: Herman J. Cohen

The prosecution’s fifth witness, former Assistant Secretary of State Herman J. Cohen, began his testimony toward the end of the afternoon. He described his educational background for the jury, and told them that he was in the Army for two years before spending 38 years in the U.S. Foreign Service. Cohen stated that when he entered the Foreign Service, many African countries that had been colonies were becoming independent, so he thought that would be an interesting specialization; he said that he spent 75% of his career working in Africa. Cohen told the jury that he served in five U.S. embassies in Africa: Uganda; Zambia; Zimbabwe; Kinshasa, Congo; and Senegal as the U.S. ambassador. Cohen said that he was the Assistant Secretary of State for Africa under President George H. W. Bush from April 1989 until April 1993.

The witness stated that he had been to Liberia prior to the ’89 incursion. Before he was an Assistant Secretary of State, he was the Senior Director for Africa with the National Security Council, and in 1987 accompanied then-Secretary of State George Shultz when he visited five African countries. Liberia was the first, Cohen said, and they spent three days there. Cohen recalled meeting President Doe and attending meetings and social events.